- FELIX

Article

13:37, 14.07.2025

In recent years, we've often heard various expressions and slogans claiming that the video game industry is "dying," with different people attributing different factors and arguments to this idea. Today, hot topics in gaming are not only about graphics, FPS, optimization, microtransactions, and other technical components that affect the perception of the game itself but also about game ownership rights—a rather specific and not always obvious topic, especially when legal aspects are rarely addressed.

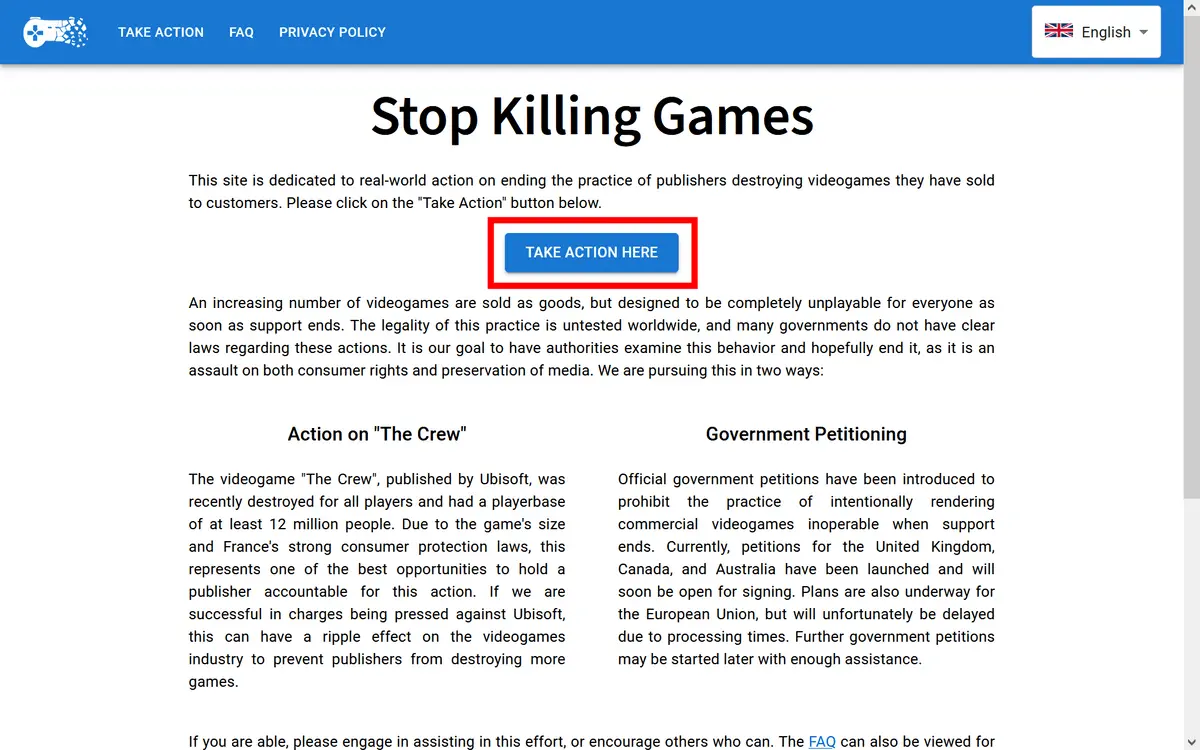

This is where the movement Stop Killing Games, led by YouTuber Ross Scott (known as Accursed Farms), comes into play, becoming the focal point of tension in the discussion: what rights do players have after purchasing a digital game?

So let's delve into what this campaign is, where it originated, and what it aims to achieve.

What is Stop Killing Games?

The Stop Killing Games movement is an initiative launched by video game consumers demanding that publishers maintain access to games even after servers are shut down—especially if the game was sold at full price. The idea behind the movement is that if a company takes away access to a game people have already paid for, it's not just inconvenient—it's a form of digital destruction.

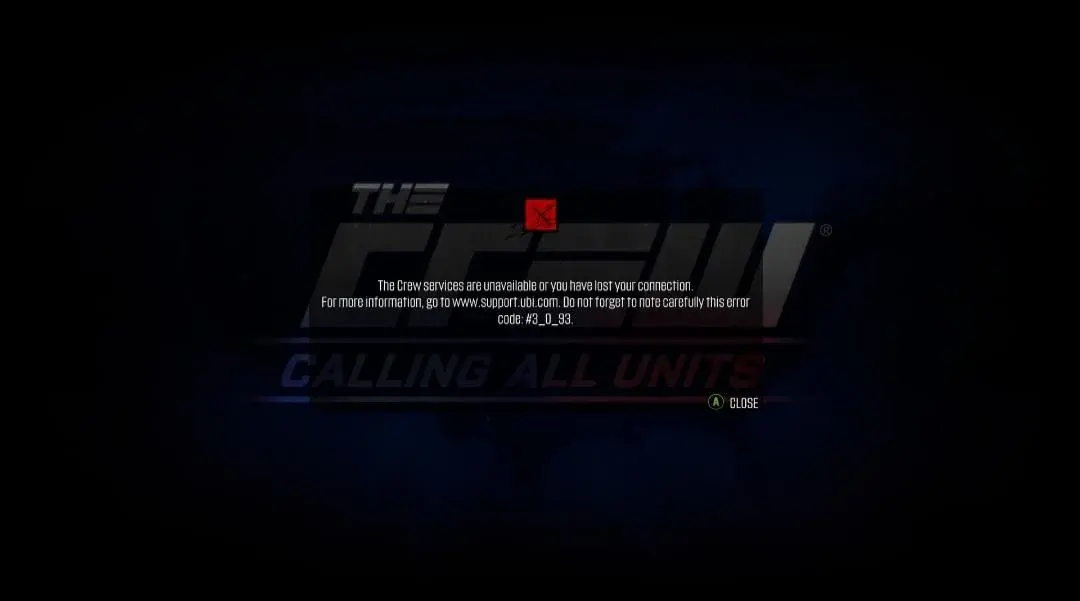

The campaign kicked off in April 2024 when Ubisoft shut down The Crew—a racing game with online dependency that sold over 12 million copies. Despite having a single-player mode, the game became completely inoperable once Ubisoft turned off the servers.

This wasn't the first game to "disappear," but this situation became the most public and painful, clearly highlighting a problem that had been building up for years. Players perceived it not as an isolated incident but as a systemic flaw—the illusion of ownership in the digital age. The situation with The Crew once again raised the fundamental question: did players truly own the game?

Who is Behind the Stop Killing Games Movement?

Ross Scott, known for the Freeman’s Mind series, has been involved in media preservation for many years. His campaign Stop Killing Games is not just a series of YouTube videos but a legal and political initiative that includes a petition within the European Citizens' Initiative—one of the few tools that can actually change EU legislation.

Ross's argument is clear: games sold without a clearly defined expiration date should not just disappear. The current system relies too heavily on the "goodwill" of publishers and doesn't guarantee that your gaming library will remain yours in 5, 10, or 20 years.

Why The Crew Became the Flashpoint

The Crew was the "spark." Ubisoft's decision to shut down the servers without an alternative led to all players—even those who played solo—losing access. They couldn't even launch the game. And this despite the fact that:

- the game was sold on platforms like Steam and Ubisoft Connect;

- it required a constant internet connection;

- it had no offline mode;

- it was still used by thousands of people.

The outrage was not just about the game's disappearance but also about the precedent: a publisher can destroy a product that has already been paid for—without an obligation to preserve it or refund the money.

What the Stop Killing Games Movement Actually Demands

Despite the simple slogan, the campaign has clear and practical goals. It doesn't demand the eternal preservation of all online features—it's about reasonable access to purchased games even after official support ends.

The main demands of Stop Killing Games include:

- the presence of offline modes in games with single-player campaigns;

- legal protection against sudden server shutdowns that make purchased games inaccessible;

- permission to create private servers if the developer no longer supports the game;

- recognition of digital ownership—the idea that buying a game should grant permanent access, not a temporary license.

This movement doesn't demand that developers support games forever and doesn't aim to punish studios for closing outdated projects. The goal is consumer fairness and long-term access: those who bought a game should be able to play it—without time restrictions.

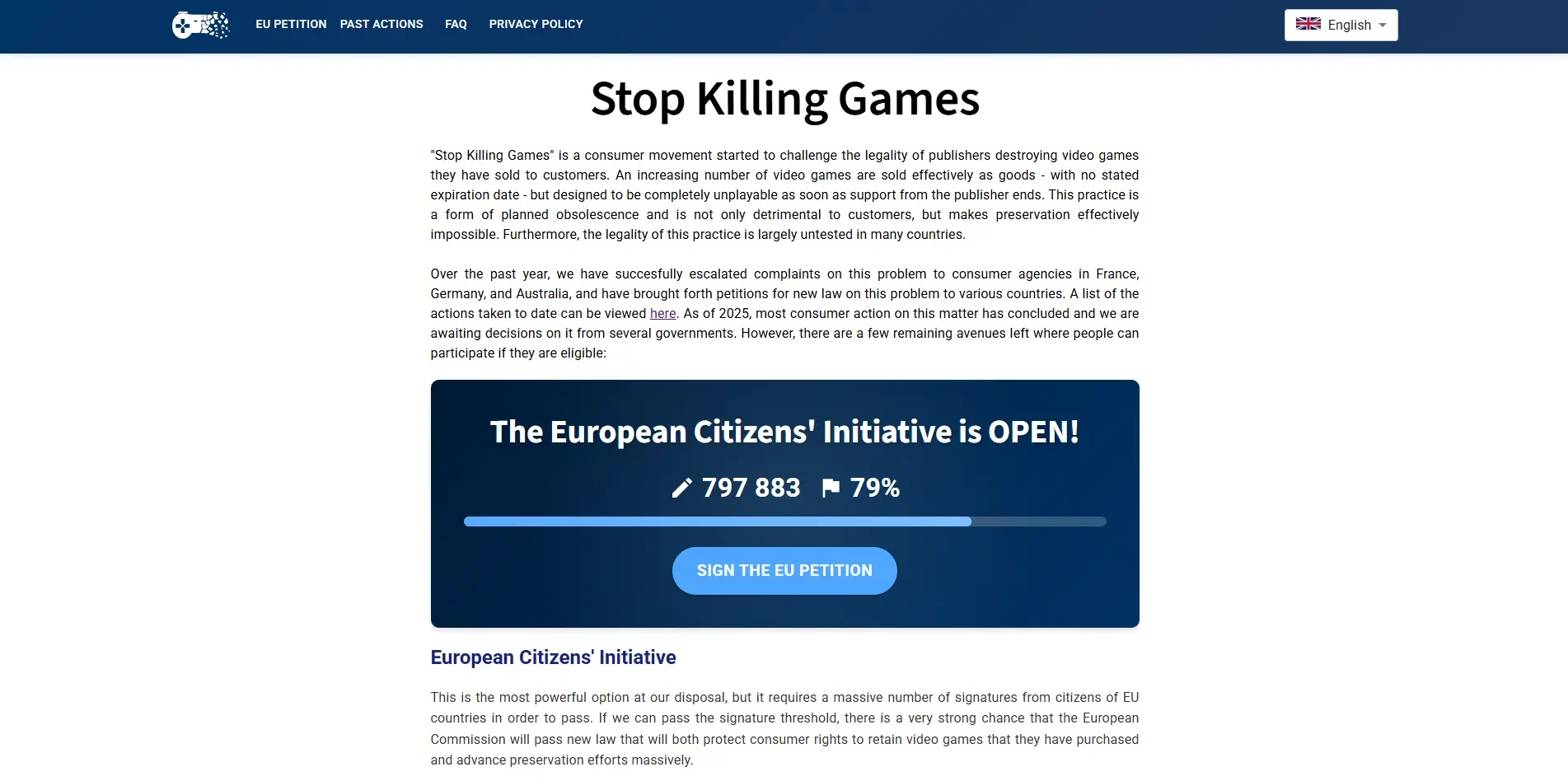

To achieve this, the campaign combines legal initiative and public awareness. Ross Scott launched an official petition within the European Citizens' Initiative—a powerful mechanism that could potentially lead to new legislation in the EU. If the petition gathers the necessary number of signatures by the end of July 2025, it will be the first serious step in legal protection for digital gaming.

This is both a matter of preserving cultural heritage and protecting consumer rights. After all, today games are not just entertainment but also a form of modern digital art and, in some cases, an investment.

Criticism and Conflict with Pirate Software

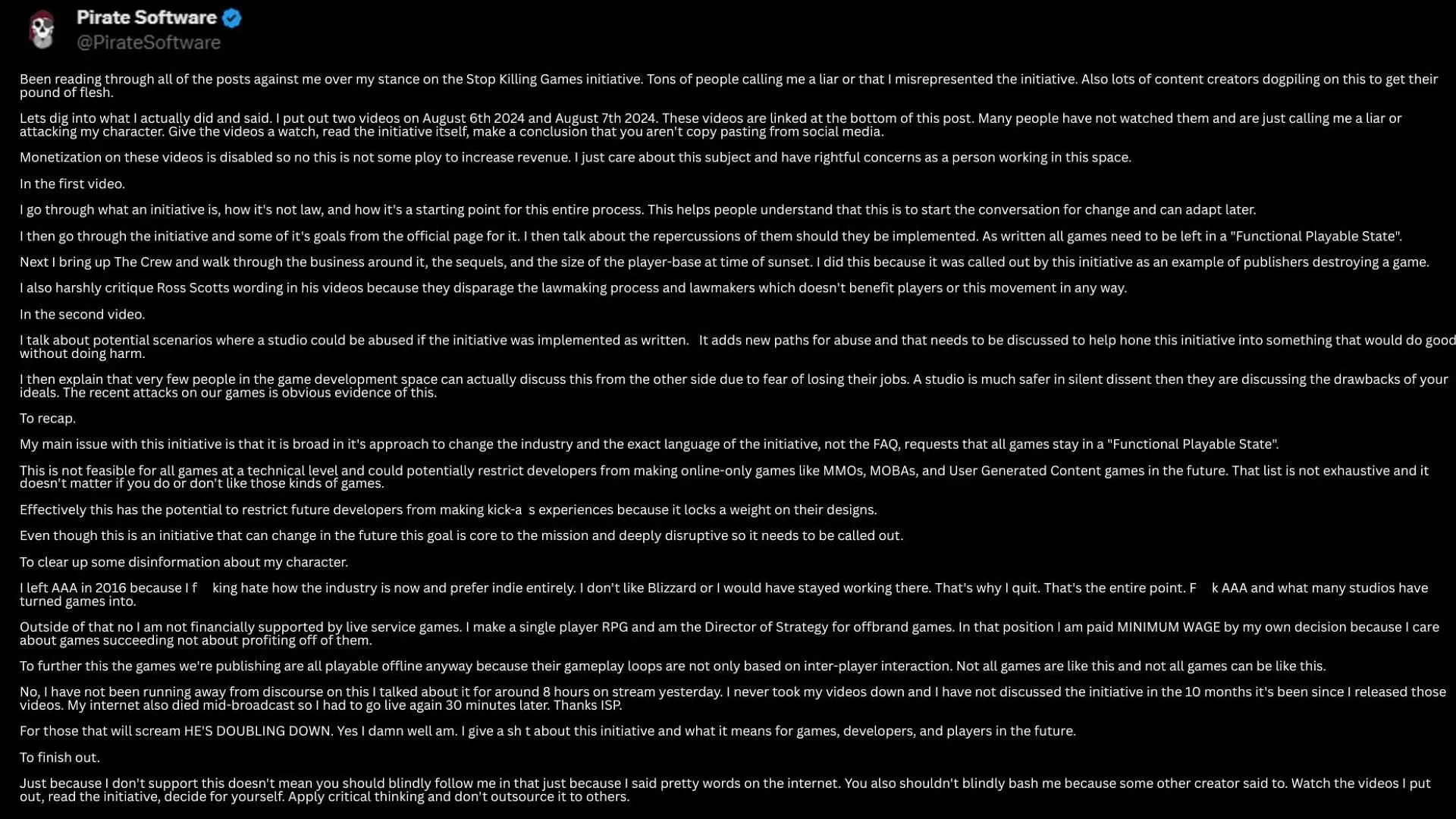

Not everyone agrees with the movement's goals or methods. One of the main critics of the campaign is independent developer and streamer Pirate Software (real name Jason Thor Hall), who released a video sharply criticizing the initiative. He called it vague, unrealistic, and potentially creating excessive financial burdens for small studios and leading to legal complications.

His main concerns:

- the initiative could create legal pressure on small studios;

- not all games can easily be converted to offline or have their server code opened;

- it could lead to excessive regulation that stifles innovation.

According to Pirate, the requirement for every game to have a preservation path after server shutdowns could be detrimental to small developers. He also pointed out that the initiative distracts from more pressing digital rights issues.

The criticism hit the Stop Killing Games campaign hard: the number of signatures decreased, misunderstanding grew, and many gamers stepped aside.

Ross Scott responded directly, releasing a detailed video response debunking all the claims and accusations made by Pirate Software. He explained that the campaign's goal is not eternal game support and not an attack on small studios. It's about minimal guarantees for players—especially in cases where the game was sold without a clear expiration date.

The discussion between the two creators quickly turned into a public feud. Part of the community accused Pirate Software of derailing the campaign at a critical moment. Ross even claimed that this was why the number of signatures on the petition noticeably decreased. Meanwhile, Pirate Software's own game, Heartbound, began to be boycotted by players who felt betrayed.

Why This Matters: The Digital Ownership Dilemma

This issue is much broader than The Crew, Ross Scott, or Pirate Software. At the heart of the Stop Killing Games movement lies a crucial question of modernity: when you buy a digital game—what exactly do you get?

Unlike physical media, digital games can be removed at any moment. They often depend on servers, accounts, or DRM systems that can be deactivated. Due to this fragility, video games are extremely difficult to preserve for the future. When a publisher turns off a game—there's often no legal way to play it again. And without access to the source code or server side—even the best preservation efforts are powerless.

Books, movies, and music have libraries, archives, and established preservation institutions. Modern video games do not. Hundreds of games from the 2000s and 2010s are already completely lost, and players are forced to turn to piracy or emulators to relive the gaming experience. This is not just a consumer rights issue—it's a cultural catastrophe.

Status of the Petition and Achievements of Stop Killing Games

As of July 2025, the European Citizens' Initiative petition has gathered over 75% of the required signatures. As the deadline approaches, it's hard to say whether it will achieve its goal. But even if it fails, the movement has already accomplished something important—it has made the preservation of digital games a topic of global discussion.

Prominent creators like MoistCr1TiKaL and SomeOrdinaryGamers have publicly supported the initiative, spreading the word on YouTube and Twitch. Even if the petition is not successful, the pressure on the industry is increasing.

The movement has already reached several critical milestones:

- putting pressure on publishers to reconsider their policies on game shutdowns

- launching a global discussion on digital rights

- bringing together gamers, activists, and consumer rights advocates

For the first time, publishers are facing a direct question: what happens to a game after the servers are turned off?

Government bodies in France, Germany, and Australia have already begun reviewing complaints filed by the initiative, indicating serious attention to the issue from consumer protection agencies.

Author's Opinion on Stop Killing Games Activities

It's clear that the Stop Killing Games movement is aimed at good intentions for the gaming community, particularly for those players who enjoy older games that have been around for many years. Even despite the moral or technical aging of games, they remain beloved by many players who still spend time in these projects or at least return to them occasionally.

However, is it possible to achieve the ultimate goal, the set objectives, and is it even appropriate? Both yes and no. Developers take certain steps, such as shutting down servers for internal reasons: unnecessary costs, changes in future strategy, license expirations, etc.

All of this may be outlined in their legal documents, which is entirely legal and makes the entire Stop Killing Games fight for consumer rights meaningless, as users "are themselves to blame for not reading this in the license agreement."

In many legal documents from developers and publishers, it is stated that players purchase not the game itself but the right to use it. This is not obvious to everyone for objective reasons, as practically no one reads this gaming documentation.

Both sides (developers-publishers and Stop Killing Games) need to reach a mutual compromise that, despite server shutdowns or other legal nuances, should provide access to the game: publish an official "pirate" version so players can continue to enjoy it, or work to prevent such incidents in the future. It should also be made clear once and for all that information about the right to use or ownership of a game should be more open to the buyer.

Whether Ross Scott's campaign will change legislation is unknown and unlikely. But it has already set a direction that could bring changes to the gaming industry.

Update from 07/14/2025

Vice President Nicolae Ștefănuță supported the Stop Killing Games initiative by signing the petition and promising to promote the issue. The corresponding post about the support first appeared in Stories on his Instagram page, after which it was noticed by users on X (Twitter).

Nicolae Ștefănuță wrote that he supports the people who started this initiative (ed. Stop Killing Games). According to him, if a game is sold, it belongs to the consumer/buyer, not the company.

"I stand with the people who started this citizen initiative. I signed and will continue to help them. A game, once sold, belongs to the customer, not the company."

— Stop Killing Games Official (@StopKilingGames) July 12, 2025

Thank you @nicustefanuta !https://t.co/Bh4KKIqN8j https://t.co/8gHEaMfsxa pic.twitter.com/crM7xb6cgC

No comments yet! Be the first one to react